In 1979, the year of the Soviet invasion, Afghanistan had no significant production of opium. But that was soon to change: The mujahedeen rebels who opposed the Red Army used opium and heroin as a source of income and expanded cultivation rapidly. Western governments considered this damage as collateral: Their main objective was to get the Soviets out of Afghanistan, and with a bit of luck the Soviet empire would suffer a bloody nose as well — payback for the humiliation of America’s debacle in Vietnam.

Today, Afghanistan produces 90 percent of the world’s opium. The global trade amounts to an estimated $65 billion annually. Most of the profits are pocketed by international crime cartels in Russia and Western Europe. In Afghanistan itself, the main beneficiaries are government officials, powerful warlords (many of them Western allies), the Taliban and — last and very much least — ordinary farmers with few alternatives.

Even as international forces start to pull out from the current conflict, most Afghan citizens still lack basic security, and the risks of civil war and further fragmentation of the country loom large. There is no doubt that Afghan opium will continue to fuel war, corruption and organized crime for many years to come.

Moreover, the impact of the opium trade is clearly not limited to Afghanistan itself: It reaches much further, deep into Europe and beyond. The old Silk Road, which once brought pearls and porcelain to the West, now brings addiction and death.

The Mujahedeen Wars, April 1993 It’s my first trip into Afghanistan, traveling by public bus together with John Jennings, the Associated Press correspondent in Kabul. Across the Khyber Pass, we find ourselves traveling through a medieval landscape: villages of mud huts, interspersed with olive groves and blossoming orange orchards. Boys with red cheeks and embroidered caps run after their goats, shooing them off the road. On the hot plains closer to Jalalabad, we see patches of land with opium poppies. The pink petals have fallen off, and the bulbs — bursting with opium sap — are ready for harvest. John tells me It’s my first trip into Afghanistan, traveling by public bus together with John Jennings, the Associated Press correspondent in Kabul.

Across the Khyber Pass, we find ourselves travelling through a medieval landscape: villages of mud huts, interspersed with olive groves and blossoming orange orchards. Boys with red cheeks and embroidered caps run after their goats, shooing them off the road. On the hot plains closer to Jalala- bad, we see patches of land with opium poppies. The pink petals have fallen off, and the bulbs — bursting with opium sap — are ready for harvest. John tells me about a program sponsored by the US Agency for International Development, which offered financial incentives to farmers who stopped growing poppies.

“The plan backfired,” John says sardonically. “Clever farmers who had never grown opium before started growing poppy to qualify for the cash hand-out.” The opium trade has also become an important source of income for many mujahedeen commanders, whose CIA funding dried up after the Soviet withdrawal. Control of the rich poppy fields and the most lucrative trafficking routes has triggered fierce battles between mujahedeen factions.

Kabul, June 1993

After work, we climb a ladder to the roof and wait for dusk. Tracer bullets shoot through the violet skies like fireworks. Every now and then, there’s a heavy blast from the hill behind us: outgoing rockets. The sound of incoming is different; first there’s a whizzing, then a sharp metallic crash. Most days, there are just two or three, but occasionally there are dozens of incoming rockets in our part of town. (In fact, between April 1992, when the mujahedeen took control of Kabul, and September 1996, when the Taliban came to power, 60,000 Kabulis were killed by rockets and other war-related violence, according to the Red Cross.)

Afghanistan, 1999–2000

The Taliban movement now controls almost the whole of Afghanistan. It wants international recognition, and to that end, it has announced that it will ban opium cultivation. Will this year really see the final harvest?

I’m in Nangarhar Province. Rashid is a friend of a friend of a friend. (I can’t mention his name; he’ll be in trouble.) When we’re introduced, Rashid at first keeps fiddling with his crocheted cap, eyes cast down, not used to looking an “unrelated” woman in the eye. He will guide me around the poppy-farming communities of Nangarhar. “Where I live,” he says, “everybody grows opium.” We leave the main road and continue along a dirt track. Behind olive groves, a vast patchwork blanket of white, pink and purple unfolds. As far as the eye can see, there are hectares of blossoming poppies and fields with young seedlings where men, women and children are busy.

In the cities, women aren’t allowed to work, and they have to cover up in all- encompassing burqas to hide them from “unrelated” men. But in the countryside, ironically, where the power base of the Taliban lies, they are far less strict. It is impossible to work in the fields wear- ing a burqa — and besides, in the village, everybody knows and is related to everybody else. Even in Talib logic, women don’t have to cover up for family.

Rashid takes me to a woman he calls Khala (aunt) Gul. She is Rashid’s maternal aunt. With her husband and children, she is thinning out the densely packed young poppy seedlings. As she continues to take out handfuls of young shoots, Aunt Gul can’t stop throwing her head back and cackling: It’s clearly hilarious to have a visitor from abroad in her field. She offers me the bowl full of freshly picked poppy shoots. “Here, have some! It is good for you,” she says. Then she shares a recipe with me: “Just wash the greens and eat it as a salad, or use it like spinach with a bit of oil and garlic.” Rashid reassures me: “Don’t worry,” he says, “these young plants don’t contain toxins.”

The rest of the family stoically continues their work on the little plot of land. There is no time to waste. Most small farmers are heavily in debt: They borrow money from middlemen whom they pay off with the harvest. Many farmers get trapped in a cycle of debt and can find themselves forced to increase cultivation even further, creating a vicious circle. “We don’t get rich,” says Amir, Gul’s eldest son, “but it still pays more than other crops.” He is not bothered by criticism that his harvest eventually be turned into heroin that will cause harm to others. “We were given war by the Americans,” Amir says, “and this is our gift in return.”

New York, 2000

About nine months before 9/11, the United Nations Security Council issues a resolution decreeing that all states shall take the following measures: … To close immediately all offices of Ariana Afghan Airlines in their territories; … To freeze without delay funds and other financial assets of Osama bin Laden and individuals and entities asso- ciated with him; … [To demand] that the Taleban, as well as others, halt all illegal drugs activities and work to virtually eliminate the illicit cultivation of opium poppy, the proceeds of which finance Taleban terrorist activities. (Security Council Resolution 1333, December 19, 2000).

2004, Tajikistan

Smuggling routes from Afghanistan lead via Pakistan and Iran into Turkey and the Balkans, or through the northern route via Central Asia and the Caucasus to Russia and the West. Afghanistan’s neighbors are trying to stem the increasing flow, but opium and heroin are being smuggled in every conceivable way: Drugs have been found in fuel trucks, coffee packaging, cat-food wrap- pers and baby diapers. Or the trafficker might opt for the low-tech solution, floating across the Amu Darya river on inflated animal skins.

Further west, we meet a Tajik Army unit at Border Post No. 7. They earn the equivalent of $20 a month — a fifth of their Russian colleagues. The Tajik commander, Captain Dorojev, doesn’t want to talk about his exact salary, merely comment- ing that it is “enough to live on. We guard the border out of patriotism,” he adds. Major Shapirov, one border post further on, doesn’t want to lose face either: “I’d rather you didn’t take pictures during lunch. We don’t have meat today.”

Afghanistan, 2004

Local poppy farmer Juma Khan proudly is showing me his new motorbike. “It cost $2,400. You want a ride?” he asks.

He drives around the field and soon gets stuck in an irrigation ditch. When he returns, Juma explains how the free market arrived in Balkh: “First we had the Taliban. They were really tough. And then we had [local ethnic] Uzbek and Tajik looters who robbed everything we had. But now we have democracy, so we grow poppy.” During the harvest, the field workers lick their opium-covered fingers. In essence, everybody harvesting is addicted. “But it’s all right,” says another worker by the name of Charis. “If you drink buttermilk with herbs, you stay healthy.”

Albania/Kosovo, 2008

Every year, 100,000 kilos of heroin transit the Balkan route. Despite claims in Albania and Kosovo that they are losing importance as a smuggling route, Interpol, the FBI and the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) still consider organized crime in this region a growing threat.

In Albania’s capital, Tirana, we interview a Western analyst of the Albanian and Kosovar security services. He’s very pessimistic.

“Ever since Watergate,” I ask, “the classic question has been, ‘Where is the money?’” “Well, if you have a look out my win- dow,” the analyst answers, “you will see all those luxury cars and construction sites. That should give you a fair idea. This is a money launderers’ paradise.”

“It’s as simple as that? All those glass towers, the new offices, the shopping malls and all those colorful apartment blocks on the Dürres coast are built with laundered money?”

“The entire Dürres coast was built with laundered money,” he replies. “All the apartment blocks. Totally. Completely.”

“Is it even possible to stay away from crime when you’re in Albanian politics?”

“Not at this stage, no. Of course, a small dealer who gets caught will not have connections with politics—but at a higher level, everyone is connected. To get power and to stay in power, especially in a poor country, you need money,” he adds. “I remember the election campaign for the mayor of Tirana. I could follow this from my window: big lights, billboards, advertising. The estimates were that the campaign cost at least €10 million. Where is that money coming from?”

Vienna, 2009

In its official report Addiction, Crime and Insurgency: The Transnational Threat of Afghan Opium (2009), the UNODC states that more Russians die from drugs every year (at present, 30,000 to 40,000 annually, according to government estimates) than the total number of Red Army soldiers killed during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the ensuing seven-year occupation.

Kyrgyzstan, June 2009

The amount of heroin entering Kyrgyzstan has tripled in just one year, while the moribund economy has forced thousands of young Kyrgyz women into the sex industry. These two facts are actually related: The growing drug trade brings with it a rise in organized crime of all sorts, including the trafficking of women from Central Asia to Europe and the Middle East. Increasing numbers of girls are being infected with HIV/AIDS. Robert and I decide to travel to Osh, the second-largest city in Kyrgyzstan and one of the main transit points for Afghan heroin.

Ninety percent of the saunas in Osh are used for prostitution. We’re sitting in a sparsely furnished room in the Jetigen Sauna downtown: a table, some chairs and an old sofa, and in a corner a mirror lit with a bare light bulb. This is where the girls wait for customers. Many are from Uzbekistan. They say they can go back there anytime they want to start a new life. Ferangiz wants to have her own cake shop, and Negora wants to open a hair salon … when they return.

Eventually. Talking to them, it is as if we are all playing parts in a play. The girls spin out their dreams, and I say, “That’s wonderful,” because I don’t want to tell them that I can’t believe in their plans. They are from around Andijan, the biggest city in the poverty-stricken Ferghana Valley. It was here in 2005 that state forces controlled by the iron-fisted Kyrgyz President Islam Karimov massacred hundreds (if not thousands) of anti-government demonstrators. What could these girls possibly go back to?

We have been there less than an hour, but the door keeps opening and a man keeps sticking his head in: Are we not done yet? Will we be long? When, after numerous disruptions, Robert and I decide to leave, we have to jostle our way past a row of men pressing against the door. The queue leads all the way down the passage to the street in front of the sauna. I realize these men are all customers waiting their turn. They will all have to be serviced by the two girls we have just spoken to.

The man who kept interrupting us was not the girls’ manager, as I thought — just the first customer in line.

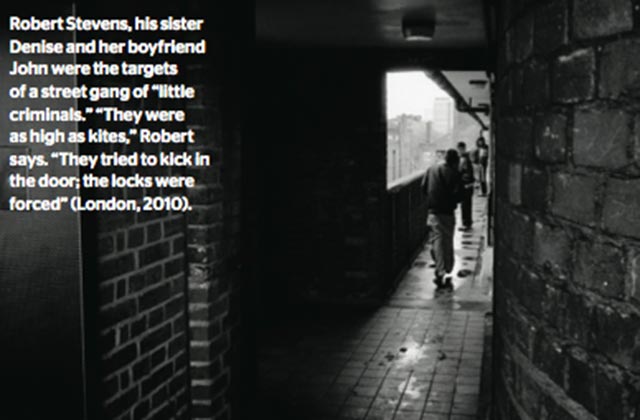

London, 2010

Back in the mid-1990s, when opium production in post-communist Afghani- stan first boomed, East London became flooded with cheap heroin. The price of a fix fell by a third, and dealers expanded their customer base by handing out free samples near schools.

A former British policeman considers the fight against drugs as lost. “It’s too late now,” he says. “It’s spiraled way out of control, because it takes people out of poverty. You could earn lots and lots of money compared to somebody who has a nine-to-five job and works his butt off and gets nothing for it at the end of the day. The others are making thousands of pounds in a week and are very content. Buying themselves all the luxury cars and homes — they’re on the property ladder now. Some of them have got legitimate businesses, but built on illegal money. And when you ask, ‘Where did you get your money from?’, he’s never going to tell. But we know where the money came from and what he built his fortune on.”

At the same time, he adds, “a dealer can be known as a reputable person. He does everything he is expected to: He is a family man. He is a dad. He takes his children to school. So he does everything he should, but he deals on the side. He makes a bit of money. He doesn’t cause any problems to anybody. He just gets on with his life, and the community are turning a blind eye to it as long as the dealers are not giving them problems.”

Vienna, 2012

The UNODC has published its latest opium surveys. In recent years, Afghan poppy production has declined from a peak of 8,200 tons in 2007 to 3,600 tons in 2010, mainly because of plant diseases. However, the basic rules of supply and demand still apply, so the scarcity of opium after the blight triggered a spectacular price rise.

In 2011, farmers could earn 11 times more from cultivating opium than wheat, result- ing in a 61 percent increase, to 5,800 tons. Last year, the harvest dropped sharply once more, to 3,700 tons, again because of plant diseases. There’s no reason for optimism, though: In 2012, poppy cultivation covered 154,000 hectares –18 percent higher than the 131,000 hectares recorded the previous year.

No doubt this story will continue…