By Steve Bloom

“The bus was busted!” HIGH TIMES Executive Editor John Holmstrom informed me as I walked into the office, only hours before my train to Toledo was scheduled to leave. It was March 28th—just four days before the Hash Bash, the main event on the spring Hemp Tour. I was planning to catch up with the bus in Toledo, Ohio, then hitch a ride to Lansing, Michigan, for a rally on March 30.

“What happened?” I asked. John had spoken to Ben Masel, the Hemp Tour’s primary organizer. “They tried to search the bus in Bowling Green [Ohio]. Someone was arrested and they towed the bus away,” John explained. “That’s all I know.”

The white Hemp Tour school bus had made the rounds during the previous fall’s Hemp Tour.

It wasn’t exactly psychedelic, but it certainly stood out. I was worried that the bust would grind the three-month Hemp Tour to a halt. I was also concerned that one of my friends had been arrested. With this sketchy information in mind, I left the office, walked over to Grand Central Station, and boarded my train. Next stop, Toledo.

March 30

Before leaving, I call a number in Toledo that was given to me by Doug McVey, who along with Rick Pfrommer and Debbie Goldsberry (one of the Hemp Tour’s key coordinators) wrote up the Hemp Tour ’90 Organizer’s Manual. A woman named Lara answers and promises that someone from the Tour will meet me at the train station when I arrive at 7 AM. I find that hard to believe. But believe it or not, a familiar white VW van is waiting for me as I walk out of the Toledo station that rainy morning. Ben is driving, and Monica, Shan, and Kevin are crowded into the back. Sort of a guest of honor, I’m given the passenger seat.

I quickly learn that the bus is in the possession of Debbie and members of Red Fly Nation, a hot new band from Kentucky that joined the tour in Lexington a week ago. But there’s another problem: The bus won’t run. Fortunately, Amazin’ Dave (from last year’s HIGH TIMES psychedelic bus trip to Ann Arbor) is on the scene, fixing the transmission so the bus can at least make it to Ann Arbor by the 1st.

So what happened in Bowling Green? Shan Clark, a veteran of the fall Tour, explains: “We had to park pretty far away from the rally, near a school. A cop named Cowboy, who wears a cowboy hat around Bowling Green, watched us unloading our material. Paul [Troy] was asleep on the bus while the rally was going on, and two cops knocked on the door at about 2:45 PM. They said they were coming on the bus. Paul said, ‘No, you’re not. I’m afraid you need a search warrant.’ They threw him out of the bus, onto the ground, and handcuffed him—when we saw him, he had a bloody nose and his hands were purple from the cuffs. They impounded the bus and then went ahead with a search. When we got to the tow yard the next day, the bus was trashed. They ransacked our bus, went through all our bags, and found two seeds. That’s been the low point so far.” Paul was freed on $100 bail (he pleaded no contest and accepted a year’s probation); the bus was fined $10 for a crack in the windshield and charged $50 for the tow. As far as the rally on the campus of Bowling Green State University was concerned, 500 people came to hear the news about how hemp can save the world and why marijuana should be legalized.

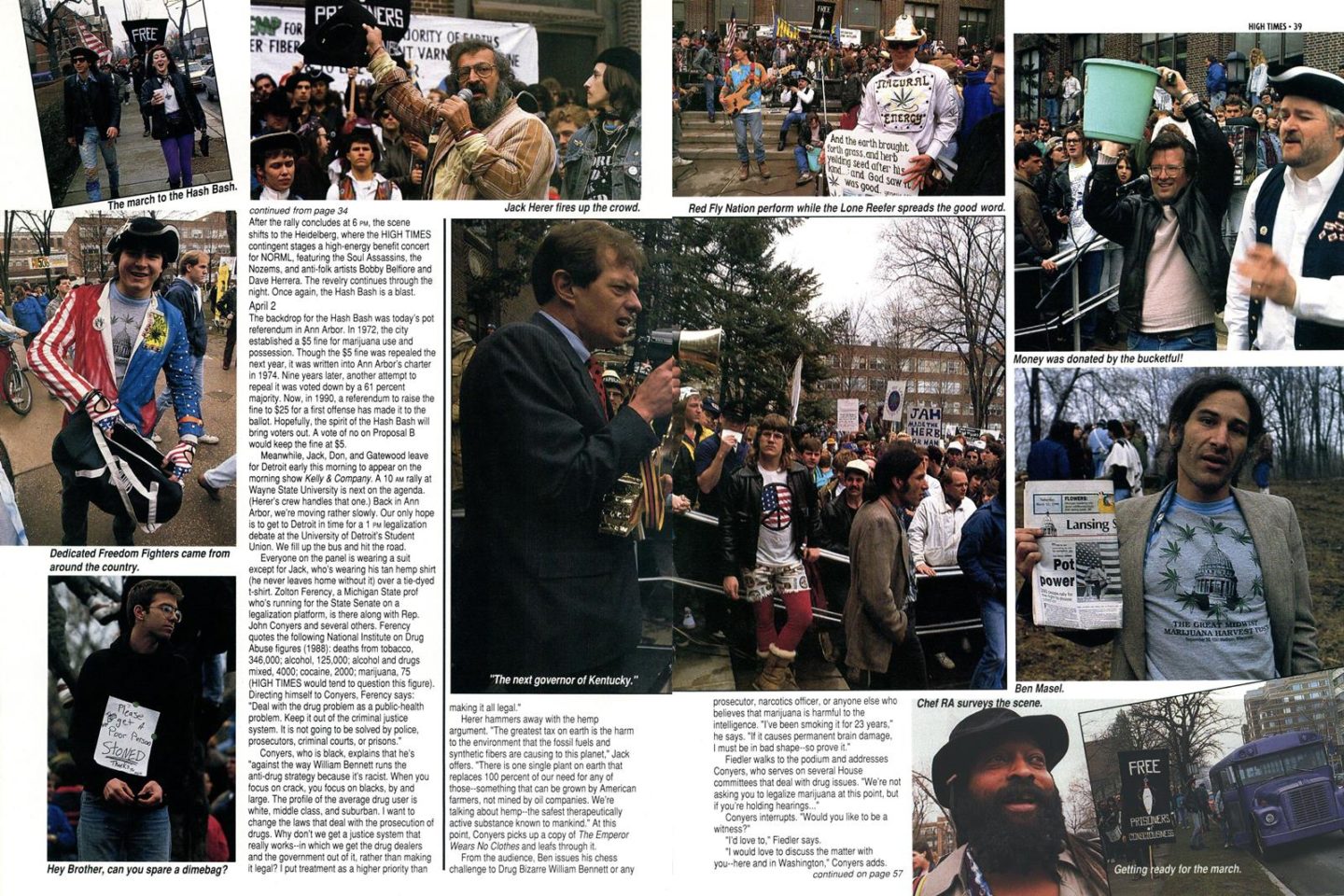

As we drive north to East Lansing for today’s rally, the rain subsides. Somehow, Ben finds Valley Court Park, where the rally is being held. Large black-and-white banners proclaiming HEMP FOR THE OVERALL MAJORITY OF EARTH’S PAPER * FIBER * FUEL * FOOD * PAINT * VARNISH * MEDICINE AND TO LIVE LONGER, OR THE GREENHOUSE EFFECT-CHOOSE ONE and the simpler HEMP FOR VICTORY (as well as a huge American flag) are already hanging from a baseball cage. These signs can only mean one thing: Jack Herer is here.

The burly, gruff-voiced author of The Emperor Wears No Clothes preceded our arrival by half an hour. His team, which includes Maria Farrow, Willie, Nelson, J.S. and Brenda, quickly posted the signs and are already selling books, stickers, and hemp clothing. In a particularly impassioned fashion, Shan introduces Jack to the spring break crowd. Waving a copy of The Reign of Law, which was printed on hemp paper, Jack ignites sparks with this fiery commentary: “We only have to be committed to the ideal that no human being on earth will ever go to prison again for a natural substance. People aren’t aware that the government has outlawed vegetables. There should be no laws against natural things. We have to drive a stake through the heart of prohibitionism.”

NORML’S National Director, Don Fiedler, also speaks, as do Ben and several locals. A band named 47 Tyme follows the speakers. This causes a problem. Seems that just beyond the park is a senior citizen’s residence. After receiving a few calls about the noise, the police decide to make their presence felt. Ben engages in conversation with them, then is told that someone has to accept the charge of disturbing the peace. Like a good Hemp Tour trooper, Ben takes the fall instead of the local organizers. He’s driven to the stationhouse, pays a $25 fine, and returns to the rally. No big deal. But it’s another reminder that there’s always a price to pay in the rally business.

March 31

It’s Hash Bash weekend, and Freedom Fighters from all over the country are beginning to converge on Ann Arbor. The first sight we see when we leave our hotels is a shiny purple bus in the parking lot. We decide to investigate. Inside is the West Virginia Freedom Fighter contingent, led by Roger the shaggy-bearded driver. Kind bud they call “hackweed” is being passed around. A coughing siege ensues. Now we know why they call it hackweed.

The morning papers bring good news. “Judge OK’s U-M Pot Rally Permit-Says U-M Violated Free Speech,” reads the front-page headline of the Ann Arbor News. In October, the University of Michigan granted NORML a permit to hold the Hash Bash at its traditional location—on the campus’ Diag. But in February, the school rescinded the permit. Fortunately, Washtenaw County Circuit Judge Donald Shelton recognized the impropriety of that decision and restored the permit literally at the 11th hour. “The University’s mishandling of the NORML permit application completely undermines its contention that any danger presented by the NORML rally is ‘clear’ or ‘present,’” the judge ruled.

But first things first. Saturday’s reserved for the first annual Freedom Fighters convention. Roger’s purple bus carts dozens of FFs to the picnic-style meeting, where spliffs are smoked, state chapter heads are elected, Chef RA’s rasta-riffic eats are chowed, and networking and partying are generally accomplished.

April 1

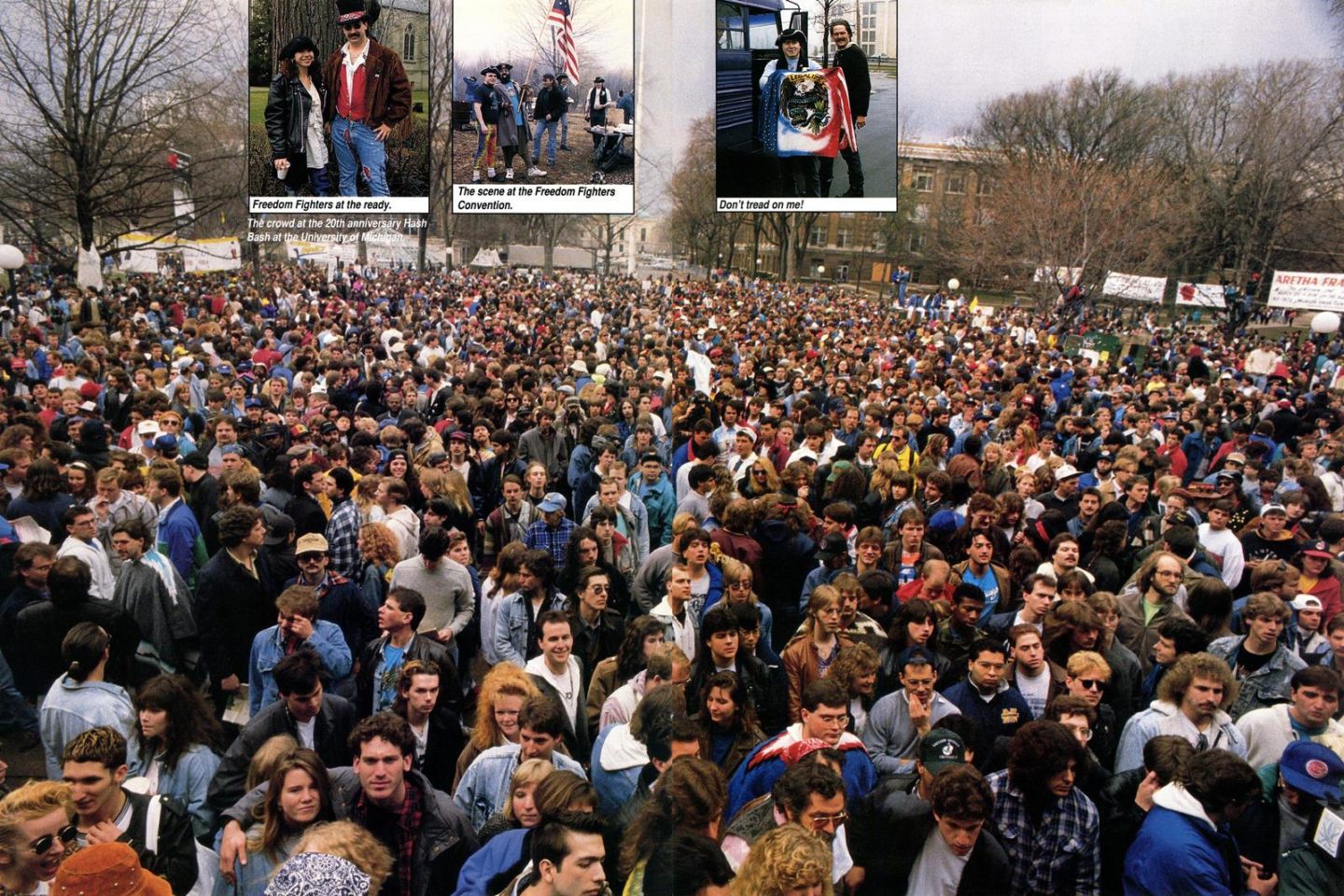

The Hash Bash begins at noon—without amplification. But thanks to the boys in Red Fly Nation, a PA is set up. Herer, Fiedler, Masel, Hash Bash organizer Rick Birkett, and Gatewood Galbraith, who introduces himself as the next governor of the state of Kentucky (he’s running in the 1991 race), all speak. Red Fly Nation plays a few songs before the PA is cut off at 2 PM. Even a midday downpour and numerous arrests can’t dampen the spirit of the 5,000-plus ralliers.

After the rally concludes at 6 PM, the scene shifts to the Heidelberg, where the HIGH TIMES contingent stages a high-energy benefit concert for NORML, featuring the Soul Assassins, the Nozems, and anti-folk artists Bobby Belfiore and Dave Herrera. The revelry continues through the night. Once again, the Hash Bash is a blast.

April 2

The backdrop for the Hash Bash was today’s pot referendum in Ann Arbor. In 1972, the city established a $5 fine for marijuana use and possession. Though the $5 fine was repealed the next year, it was written into Ann Arbor’s charter in 1974. Nine years later, another attempt to repeal it was voted down by a 61 percent majority. Now, in 1990, a referendum to raise the fine to $25 for a first offense has made it to the ballot. Hopefully, the spirit of the Hash Bash will bring voters out. A vote of no on Proposal B would keep the fine at $5.

Meanwhile, Jack, Don, and Gatewood leave for Detroit early this morning to appear on the morning show Kelly & Company. A 10 AM rally at Wayne State University is next on the agenda. (Herer’s crew handles that one.) Back in Ann Arbor, we’re moving rather slowly. Our only hope is to get to Detroit in time for a 1 PM legalization debate at the University of Detroit’s Student Union. We fill up the bus and hit the road.

Everyone on the panel is wearing a suit except for Jack, who’s wearing his tan hemp shirt (he never leaves home without it) over a tie-dyed t-shirt. Zolton Ferency, a Michigan State prof who’s running for the State Senate on a legalization platform, is there along with Rep. John Conyers and several others. Ferency quotes the following National Institute on Drug Abuse figures (1988): deaths from tobacco, 346,000; alcohol, 125,000; alcohol and drugs mixed, 4000; cocaine, 2000; marijuana, 75 (HIGH TIMES would tend to question this figure). Directing himself to Conyers, Ferency says:

“Deal with the drug problem as a public-health problem. Keep it out of the criminal justice system. It is not going to be solved by police, prosecutors, criminal courts, or prisons.”

Conyers, who is black, explains that he’s “against the way William Bennett runs the anti-drug strategy because it’s racist. When you focus on crack, you focus on blacks, by and large. The profile of the average drug user is white, middle class, and suburban. I want to change the laws that deal with the prosecution of drugs. Why don’t we get a justice system that really works—in which we get the drug dealers and the government out of it, rather than making it legal? I put treatment as a higher priority than making it all legal.”

Herer hammers away with the hemp argument. “The greatest tax on earth is the harm to the environment that the fossil fuels and synthetic fibers are causing to this planet,” Jack offers. “There is one single plant on earth that replaces 100 percent of our need for any of those—something that can be grown by American farmers, not mined by oil companies. We’re talking about hemp—the safest therapeutically active substance known to mankind.” At this point, Conyers picks up a copy of The Emperor Wears No Clothes and leafs through it.

From the audience, Ben issues his chess challenge to Drug Bizarre William Bennett or any prosecutor, narcotics officer, or anyone else who believes that marijuana is harmful to the intelligence. “I’ve been smoking it for 23 years,” he says. “If it causes permanent brain damage, I must be in bad shape—so prove it.”

Fiedler walks to the podium and addresses Conyers, who serves on several House committees that deal with drug issues. “We’re not asking you to legalize marijuana at this point, but if you’re holding hearings…”

Conyers interrupts. “Would you like to be a witness?”

“I’d love to,” Fiedler says.

“I would love to discuss the matter with you—here and in Washington,” Conyers adds.

Afterwards, Ferency tells me about his plan to legalize pot. “I’m not for taxing it. We don’t tax liquor, we sell it. In Michigan, you’re allowed to make 200 gallons of wine for personal use; I’m suggesting the same thing for marijuana. You want to grow your own pot, fine—it’s the same as wine. I deliberately came up with a plan that deals with merchandising marijuana in Michigan.

“I did that in response to our Drug Czar’s suggestion that it couldn’t be done. It can be done—very easily.”

Ferency ran for governor in 1966. He headed the state’s Democratic party for five years and was the liquor commissioner 30 years ago. He’s a lawyer by trade. “I’m the state’s best known liberal. I’ve been all over the road. I’ve been at this for 40 years. I know how it goes. I was in the anti-war movement, all the movements. What you need is middle-of-the-road presentations. People are convinced that we’re losing the War on Drugs by just reading the daily papers. They’ll listen to anybody who comes along and tells them, ‘Here’s one way we might be able to get out of this mess.’ That’s been my experience.”

Ferency’s opponent has the support of the governor. “It’s a tough struggle, it’s uphill. The governor wants that seat. All my opponent will have to do is sit in it. The governor’s raising $400,000 for her. Four hundred grand for a state legislative seat? Unheard of!” If you’d like to contribute to Zolton Ferency’s campaign—the primary is in August—send a donation to: Ferency for Senate Committee, PO Box 6446, East Lansing, Ml 48826.

Following the debate, we’re invited back to an off-campus party house. That evening, Herer is feted at a book reception at Alvin’s, a club near Wayne State.

April 3-4

Tuesday’s a rare off day for the Hemp Tour. I’m hanging out with Jack, who usually goes his separate way from the bus. He spends hours on the telephone, doing radio interviews, taking care of business. He’s a bundle of creative energy and never seems to relax.

Jack loves to see himself in print, whether he’s doing the writing or is being written about. Today’s Detroit Free Press runs a profile of Jack entitled, “Rebel With an Illegal Cause.” He’s pleased. Reporters seem to be gravitating toward the hemp issue; Jack’s book and his tireless efforts to promote the plant are the primary reasons why.

But there’s bad news, too; Ann Arbor voters, by a 53 to 47 percent majority, have decided to raise their town’s pot fine to $25.

A call from Fiedler, who’s returned to Washington, swings the mood back in a positive direction. Rep. Conyers has asked that Jack testify before the House Judiciary Committee. It’s cause to celebrate. Jack lights up a bowlful and kicks back for a few moments.

“We’re gonna win this thing, Bloom,” he barks. “No fucking way we’re gonna lose.”

Jack takes particular pleasure in converting people to his hemp message. One convert is David Hamburger, an otherwise conservative fellow who met Jack last November at the “Just Say Know” rally in Athens, Ohio. Marvin Surowitz, the organizer of the Detroit events, invited him to Athens. “Before I met Jack, I was totally on the other side—talk about quick political conversions,” says David, who is a private investor and former Bush supporter. “After the conference, I saw things differently. Cannabis, used in reasonable amounts, is an excellent natural relaxant and should be legalized. I smoke pot to increase my productivity and to take away tension headaches. But, to be honest, I find marijuana politics much more stimulating than marijuana.”

Around midnight, Jack begins mobilizing his troops for an early-morning trek to Cleveland—the next stop on the Hemp Tour. He’s scheduled to appear on The Morning Exchange TV program at 8 AM. Jack designates me as the driver. It’s an excruciating ride, but we make it right on time. A middle-aged man named Bernie Baltic is responsible for setting up the morning debate. He deposits us in a hotel and rushes Jack to the studio. Except for a change of tie-dyes, Jack’s dressed the same as he was two mornings ago. We turn the TV to channel 5 and await the debate.

The first question asked is: “Can hemp really reverse the Greenhouse Effect?” Jack rattles off all the glorious uses for hemp. The anti-drug advocate weakly challenges Jack’s hemp information and then begins reciting the standard litany about marijuana: it kills brain cells, it’s a “gateway drug,” and so on. Jack flicks these arguments away like so many marijuana ashes. From my point of view, the debate’s not even a contest.

There’s hardly any time to catch a few minutes sleep before the noon rally at Cleveland’s Public Square. Surrounded by tall office buildings and buffered by traffic, the location is perfect: No one can complain about the noise. And no one does. The rally runs five hours—Red Fly Nation plays for nearly two—without a hitch. What makes this event special is the turnout—not so much the numbers (about 400 total), but the mix of people who stop by for a quick listen. “In many ways, this has been our most successful date yet,” Ben says. “We were in front of the whole city, not just a student crowd—we had business people coming through, it was a much more mixed reception.” Even blacks, who are notably absent on the Tour, were in attendance. Thank Red Fly Nation’s funkadelic sounds for that.

John Hartman, Ohio NORML’s North Coast coordinator, who along with Ohio NORML leader Cliff Barrows organized the rally, is also excited about the “variety of people” who turned out. So where do people who attended the rally go from here? “I want them to write their representatives, take some of our literature and xerox it, pass out 100 copies here, 100 copies there—just get it out,” John says. “There’s nothing illegal about going door-to-door or standing on a street corner and handing pamphlets out. It’s a standard way of soliciting people—and the cheapest. Right now we don’t have the dollars, so it just comes down to getting out in the streets and informing people—leafletting or making calls or taking opinion polls, any contact with people.”

John invites the Hemp Tour back to his house to party and spend the night. Without people like John, the Hemp Tour would be forced to run up some pretty high hotel bills. Considering that the Tour runs on whatever it makes in sales of t-shirts and assorted products, this hospitality is invaluable.

April 5

Today’s headline in the Cleveland Plain Dealer reads, “Hemp is Given a New Twist—Fair Promotes Pot’s Many Uses.” In the article, a botanist from Case Western Reserve University admits he doesn’t know much about hemp other than its fiber is tough and it grows at a phenomenal rate. He suggests Flax, which is used to make linen and linseed oil, has similar properties to hemp.

During the ride down to the next stop—Kent State University—with Ben and Cliff, Ben says, “I want to reach the farm press and the farm researchers on this tour—make a particular effort to touch base at the agriculture schools, find the professors who might be motivated to take a closer look, and meet the kind of people who can convince the agriculture departments to give them permits to study the plant.”

Ben Masel is a professional activist. He not only runs the Hemp Tour, he also publishes The Zenger, an underground newspaper, out of his home base of Madison, Wisconsin. Ben’s style is more academic and less charismatic than Jack’s. He’s an expert polemicist and quite a good storyteller (his country twang and ironic outlook reminds me of Arlo Guthrie). Ben was the HIGH TIMES’ 1988 Counterculture Hero of the Year. I ask him to tell me when he first became politically active.

“One turning point was during the fourth grade, when we did Inherit the Wind as a class play. I was the teacher who was on trial for teaching evolution,” he laughs. “In the sixth grade, we were the first kids in the country to be bussed to integrate a black school. This was in Teaneck, New Jersey. By the 10th grade, we had been resegregated. While we were all in the same building, the classes weren’t integrated anymore. This led us to occupy the principal’s office in the spring of 10th grade. We held it for three days, and won most of our 13 unconditional demands. The principal resigned on the third day.

“Upon hearing about the shootings at Kent State, we got together a meeting of 150-200 students in the auditorium after school and we decided to call a strike. Next we heard that the Student Council wanted to join us. Then the principal came by and offered to cooperate with us if we called it a teach-in instead of a strike. A couple of days later, the Board of Education wanted to can the principal because one of the speakers at the teach-in had referred to ‘that motherfucker Nixon.’”

Appropriately, we arrive in Kent as Ben’s discussing his reaction to the events that devastated this small college town 20 years ago. Ben has a lot of personal history connected to Kent State University. He joined the May 4th Coalition in the late 70s in its efforts to prevent the University from building a gym over part of the area where the 1970 shootings occurred. They lost that battle. Perhaps today would be another.

The Hemp Tour was unable to obtain sponsorship from a student group for the rally. The Progressive Student Network balked out of fear that it would lose its registration if a legal problem arose. In addition, the school only allows use of a PA system in the plaza outside the Student Center for one hour a day—from noon to 1 PM. At 12:30, Ben plugs in the PA and begins to speak into a microphone. A crowd of about 100 congregate. By 1 PM, the local police are about to close in. Debbie warns Ben that they mean business, but he keeps talking until the police pull the plug at about 1:25. Ben races over to the PA and plugs it back in. The police grab him; the battle is on.

Ben clearly resists. They pull his hair. It takes four cops to lead Ben to their car, which is waiting about 200 feet away at the curb. The crowd chants, “Bullshit!” and “Let him go!” The cops don’t listen. In the chaos, a female frosh named Sharon Burns gets caught up in the activity. She and Ben are both arrested and taken to the nearby police station.

Sharon is charged with disorderly conduct and released on her own recognizance. Ben is hit with three charges: obstructing offical business, resisting arrest, and assault (they claim he kneed a cop in the groin). At first, we’re told that bail will be $1,250. After we make the necessary arrangements to pay a bail bondsman and drive six miles to Portage County, where Ben has been taken, we’re told the bail has been raised to $12,500. It’s fairly common to require 10 percent of the bond, but because of Ben’s long “rap sheet” and the fact that he’s from out-of-state (no doubt his previous run-ins at Kent State are also a consideration) they refuse to reduce the bond—at least until the morning. So Ben has to spend the night in jail.

Meanwhile, the Hemp Tour people are waiting for Debbie and me at a gallery on Water Street. Later on, Red Fly Nation and some local bands are supposed to play across the street at J.B.’s. There’s some anger over Ben’s decision to get arrested, but some good smoke mellows everyone out.

Water Street, it turns out, was where the calamitous events at Kent State began almost 20 years ago to the day. On May Day, 1970, Nixon announced that the US had invaded Cambodia. That night students poured out of J.B.’s and other clubs and into the streets; then they lit a bonfire and began smashing store windows. The next day, the ROTC building on the Kent State campus was firebombed. Two days later, the National Guard opened fire on the students.

Alan Canfora was there. He was shot in the wrist. He stood 50 feet in front of his friend, Jeff Miller, who took a bullet in the head. “As the guard got to the top of the hill and they stopped and they started to fire, I heard the guns go off and took a step away from them,” he tells me. “I thought, ‘Well, just in case they’re firing live ammunition, I’ll get behind a tree.’ I got behind one at the last possible second before a bullet went through my right wrist. It was the only tree in the line of fire. I’m convinced that that tree saved my life, because it was hit by several bullets and I could see many other bullets zipping through the air and ripping through the grass.”

Canfora puts today’s confrontation with the police in perspective when he explains: “Kent State remains now as it has been during the last 20 years—a very repressive institution which is controlled by the Republican interests in Ohio.”

April 6

Ben has a 9 AM hearing. A public defender named Bill Carroll shows up and asks for a reduction of the bond to $5,000. The judge agrees to that, plus he allows for 10 percent payment. Debbie counts out $500 and Ben is free.

Ben doesn’t exactly get a hero’s welcome when he returns to our Kent crash pad. There’s a noon rally slated for Athens in Southern Ohio at Ohio University. Herer has gone ahead and will run the rally. Cliff, Ben, and I again travel together; the bus is the last to leave.

For the first time on the Tour I get to see some pretty country. Southern Ohio is full of rolling hills. We take a few small roads to get there, with Ben doing the navigating. Does he regret the arrest? “Only that I resisted,” he says, proudly noting that it was his 106th arrest.

We get to Athens just as Jack is wrapping up. He applauds Ben’s arrest—’That’s how Ben teaches the kids,” Jack says. Plus, it got good press.

That evening, the University’s history and political science departments are sponsoring a debate/teach-in. It’s Jack and Gatewood versus Lois and Robert Whealy, a husband and wife prof team. The debate turns out to be quite a hoot.

The profs aren’t all that opposed. One point is well-taken: Don’t look for simplistic answers to our environmental problems. Gatewood proclaims, “I don’t apologize to anyone anymore about smoking pot. Any society that can accommodate alcohol and tobacco has room for pot.”

Later that night, Vicki Linker invites us all to her backwoods digs for a well-deserved and desperately-needed party (the type where dessert is served first). Red Fly Nation sets up in the living room and jams (I even get to play percussion on my fave songs—”Do the Feelin’” and “Strictly Wet”). Gatewood unknots his tie and opens his collar. Maria rolls the ugliest joints ever. Ben tries to recruit me to leave immediately for Indianapolis, where Farm Aid is scheduled to start in a few hours. He wants to leaflet the concert. Good idea, bad execution (the van barely made it to Vicki’s). Everyone sleeps it off.

April 7

Last stop for me—Columbus, Ohio. Everything I’ve been told to expect about the Columbus rally is right. This is one stop where there was little or no advance work, and it shows. The rally, tucked away on the campus of Ohio State University, fizzles. Hey, the Hemp Tour was due for a dud.

I’m ready to head home.

Tomorrow, Dayton hosts a rally, and then it’s off to a swing through Indiana (the Tour runs through May). Jack is packed and ready to roll. “C’mon, Bloom, you’re driving to Dayton,” he yells. Sorry, Jack, I’m booked on a flight back to New York. But he has me thinking. Should I spend just a few more days on the Hemp Tour?

At that moment, the bus pulls up; it’s being tailed by a cop. Apparently, Dean hopped a curb and is getting written up. Hey, you know what? This is one nutty Hemp Tour.

This article appears in the July 1990 issue of High Times. Subscribe here.