Social activism was built into the art of Keith Haring—one of the most widely recognized modern artists of our time. From promoting AIDS awareness to being vocally against apartheid and other issues, Haring’s art nearly always carried a message.

Haring rose from “street art”—courteously drawing with chalk instead of paint on New York subway cars, to producing art that auctions off for millions of dollars. Haring’s 1982 Untitled, for instance, auctioned for $6,537,500 at Sotheby’s New York in 2017. It’s the dream of any aspiring artist.

The Keith Haring Foundation partnered with Greenlane Holdings and retailer Higher Standards to unveil the K.Haring Glass Collection—with functional art depicting some of Haring’s iconic figures and designs. As cannabis was important to Haring, according to his closest associates, a glass art collaboration is common sense.

“I think that what we try to do with our licensing program is we try to tell different stories about Keith,” said Gil Vazquez, executive director of the Keith Haring Foundation based in New York City. “We thought of this collaboration as a way to tell the story about Keith as a weed smoker and as someone who partook in smoking weed as part of his life.”

So yes, Haring not only smoked cannabis—he preferred it. But as a workaholic, Haring knew how to time his indulgences in a way that didn’t slow down his output of art.

Vazquez continued, “He would very often smoke after he painted, never before. He would smoke after he painted to look at the paintings for a while. Truth be told—it was kind of a therapy for him as well.”

Vazquez, who is also a producer and DJ, was a very close friend and confidante of Haring—frequently speaking at events such as World AIDS Day. The Keith Haring Foundation, which he leads, was established to preserve and grow the legacy of Keith Haring and his work.

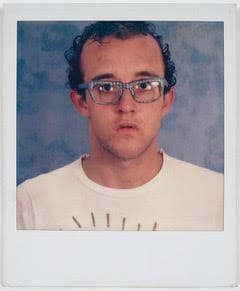

Who is Keith Haring?

Haring was born on May 4, 1958 in Reading, Pennsylvania to parents who described themselves as “disciplinarians.” His father Allen Haring was an amateur cartoonist.

Haring showed promise in art early on, and as a teen made T-shirts with things like anti-Nixon slogans and Deadhead-inspired art.

In 1978, Haring had his first solo art show at the Pittsburgh Arts and Crafts Center (now the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts). One day, Haring was nearby and noticed a piece of paper on the floor that read, “God is a dog.” The other side of the paper read, “Jesus is a monkey.” Haring said that he can’t explain why, but it triggered what he described as a punk rock attitude inside of him. He knew he had to go to New York.

Haring moved from Pennsylvania to New York that same year to study at the School of Visual Arts. In New York, he made friends, some very close, with future icons such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, Madonna, Grace Jones, Andy Warhol and Fab 5 Freddy. At the same time, he became completely immersed in the hip-hop and punk rock subcultures.

Haring hung around at places like Club 57, at St. Mark’s Place, in the basement of a Polish church, which evolved into his hangout, where he could do whatever he wanted.

On his own, he noticed empty black spaces on the subway—that seemed like they were beckoning him to draw on. So he bought a piece of white chalk and started drawing. Then he noticed negative spaces everywhere. It’s what some artists call Horror vacui, Latin for the fear of empty space—meaning a compulsion to fill open spaces with drawings and patterns.

“The street was a very important inspiration for Keith,” said Vazquez. “The subway drawings were a way to get art to the people—people that wouldn’t go to galleries and museums on their own. So he was super-innovative and recognized that these blank, black advertising spaces that were not being used were a perfect way to convey something. To draw something very quickly with chalk—parallel to what was going on at the time, which was graffiti, using spray paint directly on subway cars. So he drew inspiration from that [scene].”

Like most other artists inspired by the street, he wasn’t always accepted. “Early on, he was viewed quite suspiciously by the graffiti writers at the time,” Vazquez said. “Until he earned their respect. I think he earned their respect by getting up as much as he did. His visual language was quite simple compared to the wildstyle of the day.”

“They had to respect how ubiquitous it was. He was up on every station in every borough,” he said. “Not only that, but he was doing stuff in galleries. The guy was a relentless, relentless worker. I think the street was a huge inspiration for what he did and how he went about his business.”

Vazquez describes Haring as sort of a magnet to leaders in music and art, such as Basquiat and Fab 5 Freddy. “He really attracted like minded people and various kinds of energy,” Vazquez says. “[Fab 5] Freddy was one of those people who was a conduit between uptown and downtown. And Keith was really sort of making his bones here in downtown Manhattan. In the early 80s, there was such a fusion between really different walks of life. The punk culture was mixing with the hip-hop culture. It was such a unique time, because these movements were very nascent. The people who were dictating hip-hop and punk rock were 14-year-old kids.”

Haring’s canvas was wherever he felt like—be it subway cars or blank advertising spaces. Haring had the unique ability to incorporate minimalism in his art with a childlike spirit. His dancing figures seemed to tap into a primordial state with petroglyphs like Kokopelli or the trickster coyote. Haring was frequently arrested, but since he usually used chalk, cops were left confused, and usually let him off the hook.

Later, Haring started printing designs on buttons. He had a fascination with reprinting pop art imagery over and over again. Haring created art in subways for several years until the media really took notice.

Four years after arriving in New York City, Haring’s first major exhibition attracted Andy Warhol, along with Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg and Sol LeWitt.

Haring collaborated with fashion designer Vivienne Westwood. Westwood turned a collection of new drawings into textiles for her Autumn/Winter 1983-84 Witches collection. Haring’s friend from his New York circle, Madonna, wore a skirt from the collection, most notably in the music video for her 1984 song “Borderline.” (To this day, Madonna remembers her friend Haring on World AIDS Day on Instagram.)

It was around that point that Haring blew up—and he blew up in a big way. Haring was featured in the February 1984 issue of Vanity Fair, as well as the October 1984 issue of Newsweek.

Activism in pressing social issues was at the core of Haring’s work. Haring was featured in more than 100 solo and group exhibitions and produced more than 50 public artworks in the form of murals.

“He would very often smoke [cannabis] after he painted, never before. He would smoke after he painted to look at the paintings for a while. Truth be told—it was kind of a therapy for him as well.” – Gil Vazquez

Keith Haring Up Close

Haring had a mixed relationship with drugs, and opened up to Rolling Stone about his experiences with psychedelics in one of his late major interviews, which began at age 16.

But when crack cocaine became an obvious detriment to American society in the early ‘80s, Haring sprung into action. Haring’s friends mention that he tried nearly every drug, but obviously he could recognize which drugs should be avoided. Haring himself lost many close friends to drug overdoses.

“Crack is Wack,” one of his most recognized murals, which appeared in 1986 on the handball court at 128th Street and 2nd Avenue, was inspired by the crack epidemic and its effect on New York City.

“People take ‘Crack is Wack’ and sort of take that as a blanket to say that Keith was anti-drug,” Vazquez said. But the reality was a bit more complex than that. “Keith probably has tried every drug up until that point,” Vazquez said. “His go-to was cannabis. I think the collab is a clever nod to Keith’s weed use and his advocacy for it. Even at the time, it was underground, if you got caught with any of it, you’d be fined.”

In June 1986, he created a banner with the help of children to commemorate the centennial anniversary of the Statue of Liberty’s arrival in America. Later that year, he painted on the Berlin Wall—just as the Iron Curtain was beginning to crack in Germany. By then, Haring was one of the most popular artists in the world.

By the mid-80s, Haring’s circle of friends—many of whom were gay—were “dropping like flies.” Drugs that keep people with HIV alive simply were several years away from being developed.

Other friends succumbed to drug use or other causes. When Basquiat died in 1988, Haring wrote his obituary for Vogue magazine. Only a year earlier, Warhol died as well.

After Haring was diagnosed with AIDS in 1988, he simply started producing art at a faster rate—knowing his art would outlast himself. “I cannot ever think of a time that I heard him complain about being sick, about his condition,” Vazquez asserted. “He was very stoic about continuing to work and really being adamant that he had so much to do. I think that weed helped him through it.”

In 1990, there was little doctors could do to battle AIDS. Antiretrovirals—drugs that now control HIV very well—hadn’t been developed, for the most part.

“He got the best of everything, including weed,” Vazquez said. “He’d have the top of the top quality that you could get in New York. At the time, I wasn’t a smoker myself. So I didn’t participate, but I was always around, and saw the copious amounts of cannabis that he’d have around. He would share with his friends.”

Vazquez admits that he could picture Haring joining the medical cannabis movement, had he survived AIDS, given the artist’s long history with pressing social issues. After all, HIV was part of the driving force behind the medical cannabis movement.

“So much has happened [since then],” Vazquez said. “The attitude of the country has evolved since when Keith was alive. So hush-hush and underground. So many people smoked, but kept it under wraps. My goodness, I’m sure he would have been at the forefront of championing the legalization of cannabis as medicinal as it did help him. I’m sure if he were alive, he’d be an advocate.”

He had less than two years left after being diagnosed. His journals indicate that he didn’t know if he had five months or five years left. Haring died on February 16, 1990 of AIDS-related complications.

“Today people are able to live a fairly decent lifestyle compared to back then,” Vazquez said. “If we always lament how the advances in medicine just didn’t come soon enough for Keith to take advantage.”

In 2019, he was one of the inaugural 50 American “pioneers, trailblazers and heroes” inducted on the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor at the Stonewall National Monument in New York City’s Stonewall Inn.

The Glass Goods and the Legacy

The K.Haring Glass Collection is just one of many ways to keep Haring’s memory alive.

Designs include the K.Haring Spoon, in a hammer style pipe made of durable borosilicate glass. It is housed in a box with durable walls and foam inserts, the packaging is embellished with Haring’s signature and artistry. The K.Haring Bubbler comes with an 8-slit showerhead percolator and a fixed large bowl and downstem.

K.Haring Water Pipe is a beaker design with 7-Slit Showerhead Percolator, Thick Borosilicate Glass, Removable Diffused Downstem, Ground Glass Connection, Ice Catcher and splash guard, and fat-lipped mouthpiece. Dabbers would be more drawn to the K. Haring Rig, 90° downstem, turbine percolator, UFO-style directional carb cap, flared bucket and built-in splash guard.

Also check out Tasters, Trays, Catchalls and more featuring the art of Haring.

Haring—at least in my opinion—ranks among the other “greats” who we lost to AIDS, including Freddie Mercury, Eazy E, Ryan White and Anthony Perkins.